Joanna Rakoff: Finding the Courage, Confidence & Clarity of Mind to Become a Best-Selling Author

The author of My Salinger Year shares how keeping a clear mind and practicing presence are essential to her writing process

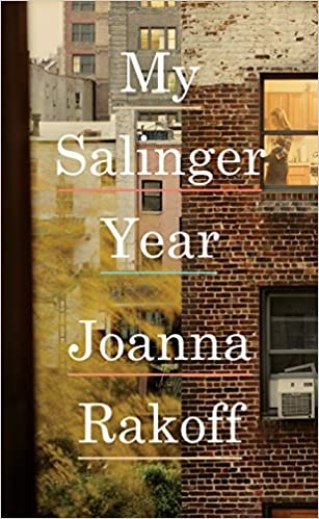

“Computers make work, rather than alleviate it,” announces Margaret, the technology abhorring head of one of New York’s oldest literary agencies in My Salinger Year. This is, of course, a movie – and one set some 20 years ago at that – but that doesn’t stop it from ringing true! New York in the mid-nineties, the setting of the film adaptation of Joanna Rakoff’s 2014 memoir, was by no means a tech-free zone, but it was definitely a world away from today’s hyperconnected smart cities. That’s why watching My Salinger Year (streamed on a laptop, naturally) left my-millennial-self feeling wistful and nostalgic for a time that I can barely remember. And I don’t just mean a time before social distancing and mask-wearing! I found myself insanely jealous of Joanna’s analog commute: imagine a time when the only people who could bother you on the train were the other passengers!

So we were overjoyed to learn that Joanna Rakoff was a Freedom fan. Not only because she is an award-winning author and journalist, but also because she has obviously spent a lot of time thinking about the evolution of technology and its impact on her creativity. Something that is all too often forgotten in the age of optimization – buried beneath the mountains of metrics, and so-called “hacks”– is the human experience and how much it can teach us. It’s one of the reasons why we love to regularly spotlight the awesome people who are using Freedom. Yes, we love to hear our talented, successful users say lovely things about us, but we also know that in order to create technology that truly enhances lives, it’s essential that we learn from those living with –and finding solutions to– the ever-evolving nature of work.

To celebrate the European release of My Salinger Year, we are thrilled to bring you this interview with Joanna, as she talks us through her journey as a writer and talks poetry, prose, parenting, and (motion) pictures!

How did you get into writing and when did you start?

As a kid, I spent an enormous amount of time reading and writing. I was that kid whose parents were always saying, “don’t you want to go outside and get some exercise?” (I did not.) I kept a diary. I wrote poems and stories, the first of which were published in my elementary school literary magazine. In high school, I wrote for every outlet that would publish me. (My youth group newsletter!!) But it took a long time for me to realize that perhaps writing could be an actual career. My parents are both first-generation Americans who prioritized financial stability over, well, happiness, I guess, and they could not tolerate the idea of my doing anything other than, say, going to medical school or law school. I just had no models, really, for how to carve out a life in media or, even worse, the arts.

For a while, I told myself I was going to be an academic. Because this seemed a socially acceptable way to be a writer. I had a whole life plan: I would get my doctorate – in literature – and get tenure at a school similar to my alma mater, Oberlin, and then, only then, would I write my first novel. But the problem was: I just wasn’t cut out for academia. Academic writing, with its jargon and emphasis on research rather than idea or analysis or, of course, narrative, utterly bored me. In my Masters program – and, later, my doctoral program – my professors kept gently suggesting I turn to writing for a general audience, rather than an academic one, meaning that I should write for magazines and newspapers.

Eventually, I dropped out of that doctoral program – a very, very hard decision, as I had a big fellowship – and switched to Columbia’s MFA in writing program, where several professors suggested, again, that I write for magazines; and offered to put me in touch with editors. I swallowed my nerves and, eventually, took them up on this. And it was through writing for magazines – seeing my byline, working with editors – that I gathered the courage, and confidence, to write a novel, which became my first book, A Fortunate Age.

What resources or tools do you use daily and have found most beneficial to your writing process?

In terms of technology, I use Freedom to remove the temptation to poke around online, which is the biggest threat to my writing. (My phone is perhaps a bigger problem than my laptop. But I use Freedom on both. )

That said, conversely, I also use technology to help me write, in the form of Tidal! I almost always listen to music while writing. Music, I think, helps me both calm down – especially at the beginning of a project, when I’m thinking, “I can’t do this!” – and amp up, or energize myself. (I listen to a lot of Okkervil River, M. Ward, and Elliott Smith. And, like everyone else, Taylor Swift. While working, I need to listen to very melodic music and also music that’s very familiar so I’m not puzzling out lyrics.) Whenever I’m having trouble getting started on work, I put on music, and it eases my entry into whatever I’m writing.

In terms of non-technology, I do a lot of writing on legal pads, and basically have a panic attack if I don’t have a legal pad (and rollerball or fountain pen) on my person at all times. Including by the side of my bed, in case I wake up with the solution to some problem of plot. I also rely, strongly, on a paper planner. Which, it’s taken me years to realize, is a complement to the digital calendar I share with my family. My favorite planner is from Papier; it looks like a bound book and, most importantly, has a lot of space for mapping out my day – more on this later – and making lists. I’ve tried not using a paper planner, but I somehow need to see everything written out in front of me.

What are your biggest distractors while writing and how do you conquer them?

My phone. Like everyone? I get into what Gretchen Rubin calls “a loop.” In which I just keep checking email, Instagram, etc. My whole life is essentially an attempt to curb this behavior. When I’m on deadline or working intensely on a book or screenplay, I’ll take social media apps off my phone, and also, sometimes apps that I use for virtually running errands for my family, like Target and Instacart. (I have three kids, two of whom are teenagers, so we always need groceries.)

Even without the apps, I can somehow find ways to fritter away time on my phone (reading The New Yorker! Looking at Christy Dawn dresses! Doing “research” for my book!) and this is, for me, where Freedom comes in. In general, I have Freedom programmed to be on from 8:30 am until 4:45 pm, and then again from 9 pm until 8 am. Because the issue is not just being distracted while writing. The issue, for me, is needing to be alone with my thoughts so that I can map out whatever essay or book or story I’m writing. And if I’m looking at Instagram at 10 pm, well, I’m not even remotely alone with my thoughts.

I also have a lockbox – I think it’s officially called a kitchen safe? – and I often put my phone in it, sometimes for whole weekends, just to give my eyes, and brain, a full break from the thing.

I can also, in full honesty, be really distracted by housework –it’s hard for me to settle down if my kitchen is a mess– and anything kid-related. It’s been hard for me to work through the pandemic with the kids home so much. In order to write, I sort of need to be my individual self, rather than my mom self; when my kids are around, all I can think about is them. Have they had lunch? Do they want to talk about The Babysitter’s Club? Do they need a hug? So, back in June 2020, I rented an outside office, and I mostly work there now.

At what point did you realize that technology was taking a toll on your productivity and time?

I’ve honestly always been aware of this. I began writing full-time –largely as a magazine writer– in late 2000 when I was in my twenties. I’m not even sure I had a flip phone back then, but I remember finding email, and the Internet, very dangerous. Writing for magazines, there was always some sort of research I needed to do. And I noticed that if I stopped work on a piece and looked up whatever bit of information right away, I’d lose a good half hour just tooling around online. So, I developed a system: When I was writing, I kept a list of anything I needed to look up. (On a legal pad, of course!) After I finished the piece, I allowed myself to go online and look everything up; then I’d slot in the missing information and adjust the story as needed. I also only allowed myself to look at email twice each day, at 9 am and 5 pm.

Years went by and technology became more all-pervasive and more invasive, and I developed even more extreme rules for my workday. By this point, I had kids and was working at a shared writers’ space (Paragraph, in Manhattan), where I would set up each day, at a desk in the back of the space that, I knew, had no phone service. When I joined the space, I’d told the owner that I didn’t want the wifi password, so I couldn’t go online from my laptop. Unless I was on deadline for a magazine, I’d stay offline all day; at around 4, I’d go for a run, then return to the space, plug my laptop into a DSL cable, and allow myself ten minutes to scan email, and ten minutes to either scan or post something (if it seemed truly necessary) on Facebook or Twitter. And then I went home to my kids.

A book is built scene by scene. Once you have all the scenes in place, you can adjust the structure, or the tone, or anything at all. But your daily work must be, essentially, enjoying being in that one scene that’s in front of you at that exact moment.

Do you have a routine or habit of writing every day? If so, how do you motivate yourself to continue?

I go through phases in which I write every day, all day. Sometimes very long phases, as when I’m intensely working on a book. I also go through phases in which I definitely don’t write each and every day but my mind is kind of gearing up to write (sifting through ideas, characters, structure, etc. as I play with my kids or bake muffins or run errands or what have you.) And then there’s what I think of as Public Mode. Which I’m in right now and by which I mean: The months surrounding a book or film release, when one is –in normal times– touring heavily, sometimes all over the world, and doing dozens and dozens of interviews and events. It’s very hard to write while in Public Mode. It takes a lot out of you. But sometimes you must. (As is the case with me, now; I have a bunch of essays due, all linked to the film.)

In terms of motivation, for me, structure is key. It can be challenging, working for oneself, especially at the start of a project. I have a friend or two who schedule their days in fifteen-minute increments; that doesn’t work for me, but what does work is breaking down my work into smaller, surmountable pieces. With my first novel, I would say, “today, I’m going to write the scene in which Dave takes a shower.” Sometimes, that scene would end up taking three days. Or a week. Sometimes, I’d have trouble getting Dave out of the shower, and I’d put aside the scene for a few days, or weeks, and move on to the next one, then come back to it. But I basically have to force myself to not think too far ahead. Or even to think about the big picture. A book is built scene by scene. Once you have all the scenes in place, you can adjust the structure, or the tone, or anything at all. But your daily work must be, essentially, enjoying being in that one scene that’s in front of you at that exact moment.

How involved were you in adapting My Salinger Year for the screen? Does the process of screenwriting differ much from writing prose? Did you change the way you worked?

I was very involved, from start to finish. When I first met with the director, Philippe Falardeau, he said, “I cannot make this film without you. If you want to just sell the rights and walk away, I’m not the director for you.” For the first year or two, I worked as a consultant on the script, which meant that Philippe sent me drafts, and I either provided copious notes or had very long conversations with him about where to go next. (Or both.) Eventually, he reached a stopping point and passed the script on to me for what is known as a “polish” (and what the producers called an “insider pass”).

The final script represents a true collaboration between us. A lot of what we did, over those three years or so, was to streamline the book –trimming characters and plotlines– and also turn some of the internal moments into external action: So, in the book, I spend a decent amount of time thinking about Salinger’s fans. In the film, we actually show you the fans. (This was Philippe’s idea and it’s one of my favorite parts of the film. Oddly, or not, many of my favorite moments from the film are those we invented in order to make the story work for the screen.

Screenwriting is, in many ways, very, very different from writing prose, because everything must be conveyed either visually or through dialogue. In a book or an essay, you have a narrator who can simply tell you what’s going on. You can have exposition. In a film, you have to be careful of having a character say too much. Which can be difficult in a film, like My Salinger Year, about a very specific industry or world. The Big Short handles this conundrum –how to explain complex financial concepts without slowing down the story?– in a truly brilliant way. (Margot Robbie in a bathtub!)

I actually started out as a poet –my MFA is in poetry– and, weird as this sounds, screenwriting reminds me, in a way, of poetry. Because it’s a bit like putting together a puzzle. And it also involves writing with very specific constraints. Which I love. The freedom of prose can sometimes be exhausting.

I also loved collaborating with Philippe. Writing is a very lonely business and I’m a somewhat social person. We had so much fun just tossing ideas back and forth. ”What if Joanna goes to DC to chaperone Salinger’s meeting with Roger?” It’s honestly been hard, going back to just sitting by myself, writing a book. I’m doing it, but I’m really looking forward to my next film project (which I think will turn out to be a tv project).

Part of my project, with the book itself, was to write about the ways changing technology has altered the way we experience daily life.

Did watching or working on the movie adaptation of My Salinger Year, which is set in the mid-1990s, cause you to reflect on how your relationship with technology has evolved since then?

YES! A million times over. Part of my project, with the book itself, was indeed to write about the ways changing technology has altered the way we experience daily life. The book begins with a scene we couldn’t keep in the film –though the director desperately wanted to; it was just too expensive to shoot– in which, on the day I was meant to start work at the Agency, a massive blizzard hits New York, shutting the entire city down. This was 1996, so no cell phones – and most people didn’t have an Internet connection at home. The Agency had a phone-tree system for notifying employees of emergencies: The president, my new boss, would call the senior-most agent, who would then call the next-senior-most agent, and so on… until they got the receptionist, the courier, and the assistants. But because I’d not yet started, I wasn’t on the tree yet! Which meant, I woke up, put on my carefully selected first day of work clothing – including a pair of very mid-1990s chunky-heeled loafers –walked to the train through feet of snow, got off the train at Grand Central, and walked up Madison Avenue to my office. Only to find it empty.

I sat at my desk, soaked to the bone, wondering what was going on. The office didn’t even have computers – if you can believe it. (This was unusual, even at the time, but not unheard of.) Eventually, my boss called –on the landline, of course– explained that the office was closed (the whole city was closed!) and that I should go home. So I left the office and walked through the city’s deserted streets –streets that were generally mobbed– completely and utterly alone, the snow tickling my face.

I began with that scene because, even in 2012, when I was writing the book, it would, and could, never happen now. Our phones are always with us, so we’re never truly alone. And we always feel the pull of social media. The need to take a picture to post on Instagram.

I miss the quiet that comes from being truly alone. From just thinking one’s thoughts. There is so much, honestly, that I love about social media –the connections with friends; the forging of new, rich friendships; the beautiful images and interesting ideas– but I desperately long for that time in which I could just experience life in an unmediated way. I miss taking a walk and being truly alone.

What advice would you offer less experienced writers – especially concerning staying productive, motivated, and focused?

I would strongly urge new writers to focus purely on the writing itself. To write the book –or whatever– that they want to read. To not think about publishing, or “building platforms,” or getting an agent, or any of that. Just write.

Conversely, I’d also say that if you feel called to write essays, or reviews, or journalism, definitely just do it. Go to journalism school, or get an internship at a magazine (if your finances allow it), or start pitching stories. Because writing those shorter pieces, on deadline, helps build the discipline needed for a novel (or any other book-length work).

Read. Read. Read all the time. Put down your f*****g phone! Reading is what makes you a good writer. By which I mean reading books –and magazines, and newspapers– ideally on paper, so that you can sink into the material without the pull of the vast online universe. (Without thinking, after a paragraph, “wait, I need to order sunscreen.” and toggling over to Amazon.)

Some of my happiest memories from growing up involve sitting around our dining room table with my parents, or my massive extended family, just talking and talking. I wanted my kids to have that same experience. To understand the pleasure of conversation.

As a parent, how do you ensure that your children are developing healthy relationships around tech use?

This is such a good question and something my husband, Keeril, and I discuss all the time. A lot of my family is in the Bay Area –my parents actually used to live right in the heart of Silicon Valley– and I remember, when my old kids were little, having dinner in Mountain View and seeing families just sitting around the table, staring at their devices. It seemed like the most depressing thing in the world to me and while I’m in no way judging anyone –who knows what stress those parents were under– I knew that this wasn’t what I wanted for my own family, my own kids. Some of my happiest memories from growing up involve sitting around our dining room table, having dinner, or Sunday breakfast –a big thing in my family, which is very New York Jewish– with my parents, or my massive extended family, just talking and talking. I wanted my kids to have that same experience. To understand the pleasure of conversation.

To that end, my older kids had far less technology than their peers. We’ve never had a video game console of any sort. They don’t have iPads. They were not allowed to play with my phone. We don’t even have a television. Though we do watch movies and shows together as a family. My older kids are now sixteen and twelve and they both have iPhones, largely because we wanted them to be able to stay in touch with their friends during the pandemic, which has been brutally lonely for them. But we have very strict screen time controls on both their phones. We force my twelve-year-old to put her phone to bed pretty early –at 8:30 or 9– which she hates, but we see the effect on her when we, for whatever reason, fail to do so.

We also allow our five-year-old to watch tv –on our laptops– only on the weekends, and only as a group activity. One of us is always with her, so she understands that television is a social activity, as it was for us as kids in the 1980s. But that’s it, in terms of technology, for her. We are pretty low-key about everything –she pretty often eats chocolate for breakfast and goes to school in her pajamas– but this is the one thing on which we won’t budge.

My whole life, in a way, is designed to keep my mind clear so I can think through whatever I’m working on.

What do you do outside of work that helps you stay productive?

Oh boy, a lot. My whole life, in a way, is designed to keep my mind clear so I can think through whatever I’m working on. I do yoga almost every day. (Here in Boston, I practice at a wonderful studio called Down Under.) When I’m working most intensely, I take a run at the end of the day, as running helps me think through problems of plot and structure in a way nothing else does. I also take a lot of walks.

I’m obsessive about sleep and sleep hygiene. I try not to look at my phone after dinner. Sometimes, because I’m a human, I fail. (And sometimes, I have work that I absolutely have to do. Promotion for the film, for instance, has been all-consuming.) But I have Freedom programmed to turn on at 8:30 pm, so I can’t just peek at Instagram or Gmail. (It turns off at either 9 am the next morning or, if I’m on deadline, 4 pm the next day.) I don’t ever bring my phone into the bedroom with me. The idea of sleeping with my phone in the room, honestly, fills me with horror. And while I do write at night, I do so on a legal pad, with a pen.

I also spend a lot of time just hanging out with my kids and my husband, talking, listening to music, dancing around the living room, and laughing. I am not a multi-tasker. When I’m with my kids, I’m with my kids. I try not to look at my phone when I’m with them – which sometimes means hiding in the bathroom or the kitchen to send a text, but I’d rather do that than sit on the couch, peeking at my phone while they tell me about their days.

I’d rather read a truly great novel, that was a lifetime in the making than a bad one –or, worse, a mediocre one– that took one year. Wouldn’t you?

What inspires you to improve your craft?

Reading. Both good and bad. My new book, The Fifth Passenger, is another memoir, but it’s a much bigger, more sprawling story than My Salinger Year, and it’s taken me years to figure out the structure, and also the narrative approach. (My editor has been very patient!). But I’m not, by nature, a memoirist. I’m a novelist. In the first year or so after I signed the contract for the book, I kept searching for memoirs analogous to mine and finding books that just…weren’t interesting to me, stylistically or in terms of narrative style.

Then, I picked up The Goldfinch. Donna Tartt is one of my favorite novelists. I’ve read The Secret History probably six times. But somehow I’d held off on The Goldfinch. Until this fateful weekend about two years ago, when I picked up and didn’t put it down for forty-eight hours. Midway through, I realized that this is what I want to do with my new book –which, though it’s a true story, has some parallels to The Goldfinch– and that this is what I’d always wanted to do.

As a working writer –someone who makes a living through writing, as I’ve done for most of my adult life– you can get very caught up in productivity. Social media, of course, makes this worse. When you’re a part of the literary world, and the publishing world, you see friends and acquaintances posting photos of their completed manuscripts, or the endless essays they’re publishing, and think, “what is wrong with me? How did X write a whole novel during quarantine?” But reading reminds you –reminds me– that I didn’t get into this game to produce. My goal was never to produce a book a year, or what have you. My goal was to write the books –and essays, and reviews– that I wanted to read. My goal was to write great books, books that would change people’s lives and make them see the world anew. And if those books take me ten years, that’s fine. I’d rather read a truly great novel, that was a lifetime in the making than a bad one –or, worse, a mediocre one– that took one year. Wouldn’t you?

What projects are you currently working on that you are most excited about?

Right now, I’m in the midst of publicity for the film, so I’m writing a bunch of essays for different publications, mostly tied to the film –a really fun one is about how I prepared to walk the red carpet when the film opened the Berlinale last year– and it’s been such a pleasure to write short pieces, after years of working almost exclusively on my new book and the screenplay. I’ve been on hiatus from magazine work for the past few years, as I felt I had too much on my plate to take on shorter pieces. But writing these pieces has made me realize that for me productivity breeds productivity. I work best when I have too much on my plate; when the ideas from an essay bleed into a review which sparks a thought for my book.

But soon, I’ll be returning to that new book, The Fifth Passenger, which has been in the works, in different ways, for something like twenty years. The story is basically this: For most of my childhood, I believed I had one sister, eighteen years my elder, with whom my parents had a somewhat contentious, or fraught, relationship. Eventually, when I was about ten, I discovered that there had been two kids in between us, but I knew nothing about them other than their names. Over the course of my life, bits and pieces of their story –and my family’s story– came out, often by accident, but I still, as an adult with two kids of my own, never knew what really happened. Until I had my third child –at the same age my mother had me– and decided to go back and investigate the story. Once that’s done I’ll –cross fingers– be adapting my first book, A Fortunate Age for television.

Listen to Joanna Rakoff on the Freedom Matters Podcast:

Joanna Rakoff is the author of the novel A Fortunate Age, winner of the Goldberg Prize for Fiction, and the international bestselling memoir, My Salinger Year, which was just released as a feature film starring Sigourney Weaver and Margaret Qualley. Rakoff’s books have been translated into twenty languages and nominated for major prizes in The Netherlands and France. She has written frequently for The New York Times, Vogue, Marie Claire, O: The Oprah Magazine, and many other publications. She lives in Cambridge, MA with her family.